Reykjavík is the capital and largest city of Iceland, located in its southwest on Faxa Bay, and the northernmost capital city in the world. The Esja massif towers 10 km north of Reykjavík. The Icelandic capital has a population of 131,100 (2020). The city is part of Reykjavíkurborg Municipality, which, in addition to the capital, includes its surrounding area and the areas across Kollafjörður Bay. The entire municipality has a population of 126,000 (2018). The Greater Reykjavík Urban Area (Stór-Reykjavík), encompassing the capital and neighboring cities, has a population of 217,700 (2018), and the entire Höfuðborgarsvæðið capital region has a population of 222,500 (2018), or approximately two-thirds of the country’s population.

Climate. On July 30, 2008, the city’s heat record was broken – it currently stands at +25.7°C. The lowest recorded temperature is –24.5°C (January 21, 1918). Since January 30, 1971, the temperature has never fallen below –20°C. The climate is subarctic (Cfc), according to Vladimir Köppen’s classification, but influenced by the warm oceanic North Atlantic Current.

Hallgrímskirkja, a viewpoint. At the southeast end of the historic center, on the city’s highest hill, stands one of the capital’s most recognizable buildings. The Lutheran Hallgrímskirkja Church was designed by Guðjón Samúelsson, and its concept evokes Icelandic nature and Scandinavian Gothic architecture. Construction took over 40 years and was accompanied by numerous controversies (for example, city councilors demanded the tower be enlarged because they wanted their church to be taller than the Catholic cathedral). The resulting church features an unusual façade, centered on a 74.5-meter-tall tower (making it the city’s tallest structure). The church is named after the 17th-century poet and pastor Hallgrímur Pétursson. In front of the church stands a statue of the famous Viking Leif Eriksson, who sailed to the shores of North America. The realistic sculpture depicts the explorer in full armor, axe in hand.

National Museum of Iceland (Þjóðminjasafn Íslands).

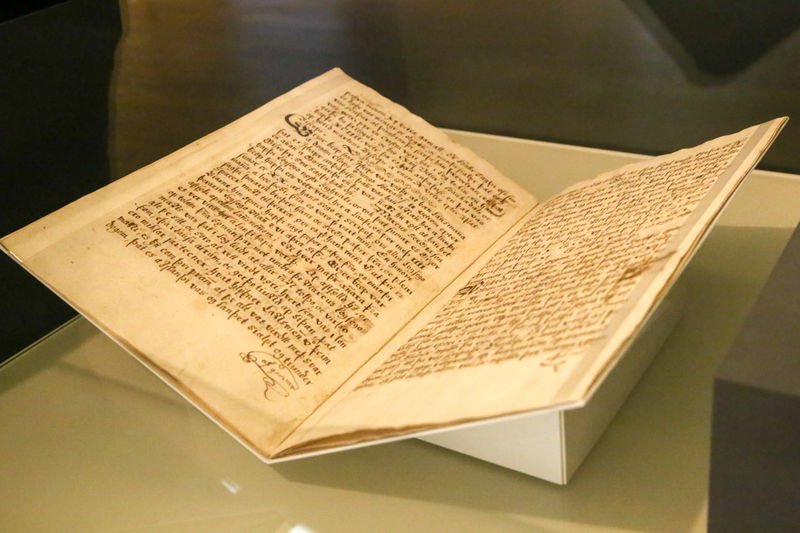

A visit to the Icelandic National Museum is a great opportunity to learn more about the history and culture of this small country. Its collections include artifacts spanning the entire history of the island – from its settlement to the present day. Exhibits are displayed on two floors. Additionally, there’s a photography exhibition. Icelanders have never been a warrior nation – they even boast of never inventing any weapons. In the initial section of the museum, dedicated to the first settlers and the Viking era, you won’t see many swords, shields, or helmets. Instead, there are votive figurines (one of which likely depicts Odin himself), jewelry, and everyday tools used in fishing, agriculture, and crafts (e.g., blacksmiths). The floor is marked with the outline of a ship that the first settlers may have used to arrive on the island. The exhibition then follows the chronology of events. We have exhibitions on the adoption of Christianity, the Reformation, life under the rule of rulers from other Scandinavian countries, regaining independence, and the construction of a modern state. Information boards (in English) provide insight into each of the most important periods in the island’s history. These are just a few examples, but the museum’s entire collection comprises approximately 2,000 exhibits. Some of the objects from the Viking era (and beyond) are unique, and cannot be found in museums on continental Europe. A significant portion of the collection consists of exhibits related to the Christian religion.

Árbæjarsafn, an open-air museum. With the arrival of the 20th century, Reykjavík’s landscape began to change. Small wooden huts and modest farm buildings were replaced by much more impressive structures. With each decade, the transformation from a small folk town to the fully-fledged city we know today accelerated. Local activists quickly realized that the heritage of their ancestors would soon be irrevocably lost. Therefore, the decision was made to create a Scandinavian-style open-air museum in which some of the historic buildings could be preserved. The chosen location was the Árbær farm (Icelandic: Árbæjarsafn), which was located outside the city at the time and had been without a host since 1948. Over the following decades, buildings of architectural or heritage significance were brought to the open-air museum, most directly from the center of Reykjavík. Currently, the museum grounds house approximately 30 structures from the 19th and early 20th centuries. These include traditional turf-roofed buildings. Many houses house exhibitions presenting the living conditions of residents from various social classes, as well as the workplaces of artisans.

The historic center. The oldest part of Reykjavík is distinguished by its low-rise buildings, colorful facades, and numerous successful examples of street art. Unsurprisingly, however, as the number of tourists increases, the character of this area is also changing – many shops catering to visitors have opened (offering souvenirs and Icelandic woolen goods), and some restaurants have introduced typically continental menus. The main artery of the Old Town is Laugavegur Street. It is lined with numerous shops, boutiques, cafés, and bars. The latter sometimes offer a piece of fermented shark for the price of a shot of alcohol, but we recommend thinking carefully before accepting an offer. For us, it was the worst thing we have ever eaten (possibly rivaled only by the Sicilian “delicacy” pane con la milza, a sandwich with spleen and lungs). At Laugavegur 23, we will see one of the most interesting examples of street art. To find the oldest wooden building in the city (and the oldest existing house), we should head to Aðalstræti Street, where the former bishop’s residence is located at number 10. Currently, the city museum hosts exhibitions inside. It’s worth noting that remains of buildings from the time of the first settlers were found directly beneath Aðalstræti Street, making it the oldest part of the city. At the intersection of Aðalstræti and Hafnarstræti Streets stands a red building with falcon sculptures on the roof. These refer to the building’s former purpose, housing Icelandic falcons awaiting export. One of the most important squares in the city center is Austurvöllur. It is flanked by two important buildings: the cathedral and the parliament. The cathedral, often confused with the more impressive Hallgrímskirkja, is the oldest church in the city. Both buildings are described in more detail later in this article. The square’s name translates as “Eastern Field.” This is no accident – over 200 years ago, peat was harvested from here to build Icelandic houses. In the early 18th century, shortly after the cathedral was built, city authorities banned grass cutting. In the following decades, the field was used for sheep grazing and as a camping site for visitors to the capital. The square took on a more representative form only in the summer of 1875, and on November 19, 1875, the first public sculpture in Reykjavík was unveiled in its center. It depicted the Danish sculptor of Icelandic descent, Bertel Thorvaldsen, a gift from the consul of Copenhagen. You may recognize this artist – he was the creator of the equestrian statue of Prince Józef Poniatowski, which stands in front of the presidential palace in Warsaw.

Lutheran Cathedral (Dómkirkjan).

As the city grew, a suitable church became necessary. The first church was built in 1787 (nine years later, it became the seat of the bishop). During the 19th century, it underwent several major renovations. The last major renovation took place in 1878. Four years earlier, the establishment of the constitution was celebrated here. Until the 1880s, it housed the State Archives, thanks to the privileged position of the Lutheran Church in the country. One of the most interesting monuments inside is the baptismal font sculpted by Bertel Thorvaldsen.

Tjörnin – Lake. A popular spot for weekend walks is the lake (or rather, a lagoon cut off from the sea) of Tjörnin. Despite being located in the very center of the capital, around 50 species of birds feed there. Feeding the local ducks has sometimes earned the lake the nickname “Iceland’s largest bread soup,” which is why city officials urge residents to leave the ducks alone. The lake is surrounded by several historic buildings. On the northwest shore, you’ll find the Town Hall (Icelandic: Ráðhús). Next to it, a terrace overlooking the water features a monument dedicated to an anonymous bureaucrat (Icelandic: Óþekkti embættismaðurinn).

Harpa is the name of a modern, fully glazed building housing a concert hall and conference center. The building is a symbol of modern Reykjavík, and it’s hard to miss it when visiting Iceland’s capital. Its glass facade is worth a glance, not only during the day but also after dark, when its glass blocks shimmer with different colors. Harpa’s facade, like Hallgrímskirkja, was modeled on the Icelandic landscape. A comparison of the two buildings reveals how much architecture has changed in less than a century. The three-dimensional glass elements of the facade, which allow light to enter the building’s interior, are particularly noteworthy. In 2013, Harpa’s designers were honored with the prestigious European Union Mies van der Rohe Award for Contemporary Architecture. The building’s name itself is intriguing, alluding to both its purpose and Icelandic heritage. The word “harpa” can be translated literally as “harp” (instrument), but it is also the name of a month in the old Norse calendar, the first day of which heralded the arrival of summer. The complex opened on May 4, 2011, and since then, it has hosted major cultural events. Restaurants and shops also operate inside. Harpa is a public building, and anyone is welcome to visit. Approaching the north wall offers a panoramic view of the bay.

The Old Harbour is now one of Reykjavík’s most visited areas. Numerous attractions await, including museums, bars, and restaurants housed in old warehouses and former administrative buildings. Popular whale-watching tours also depart from the harbour. The area has seen a number of modern developments in recent years. The port area was established in the early 20th century, when Iceland’s capital was still a small town. Construction began on March 8, 1913, and the official opening took place on November 16, 1917. The new port became the capital’s driving force. Thanks to fishing and exports, the city was able to enter a period of dynamic growth. However, recent decades have seen a shift in the island’s economy – it’s more profitable to show tourists whales than to hunt them, which has affected the character of this part of the city.

Maritime Museum, ship Óðinn. The Reykjavik Maritime Museum (Sjóminjasafnið í Reykjavík) has been established in the port area, focusing entirely on Icelanders’ relationship with the sea. Exhibitions will explore the times of the first settlers and the hardships of Icelandic fishermen, among other things. Part of the exhibition focuses on the so-called Cod Wars, which the small country fought several times with Great Britain throughout the 20th century. In front of the museum, in dry dock, sits the ship Óðinn, which patrolled Icelandic waters during the conflicts with Great Britain. It’s worth remembering that Icelanders are a peaceful nation and have never had a traditional armed force. Instead, they invented a special cutter with which they could cut the nets of foreign fishing boats.

Ingólfur Arnarson Monument. On the small hill of Arnarholl in the city center stands a monument dedicated to Ingolf Arnarson, the first Icelandic settler and legendary founder of the city.

Elliðaárdalur – the green lungs of Reykjavik and the island’s oldest hydroelectric power plant. Iceland’s capital is one of the densely built-up cities, and if it weren’t for the surrounding mountains, we might forget we’re on an island renowned for its nature. Fortunately, even in Reykjavik, we can enjoy the popular attributes of Icelandic nature. On the outskirts of the city lies the verdant Elliðaárdalur Valley, which, ironically, runs along the busy Route 41. The valley was formed over 4,500 years ago during a volcanic eruption. Two rivers flow through it, originating in the Bláfjöll volcanic mountains. Along the way, one of these rivers formed a cascading (though not very high) waterfall. This area is of significant natural value, home to several hundred plant species. The valley is also home to around 60 species of birds and a mecca for fishing enthusiasts who fish for salmon in the local river. If you look closely, you might spot one of these fish in the water. Other inhabitants of this area include black rabbits. Several walking trails are available for visitors. Walking deeper into the forest, you’ll be able to mute the noise from the street. Right next to the valley, on the eastern side of the Elliðaár River, lies one of the most important industrial monuments in all of Iceland – the island’s first hydroelectric power station (Elliðaár Power Station). The power station was commissioned on June 27, 1921. King Christian X of Denmark and Iceland and his wife attended the official inauguration. The two original turbines, the oldest in Iceland and manufactured in Sweden, are still operational in the building.

According to the so-called “Book of Settlement” (Isl. Landnámabók), the city’s founder was Ingolf Arnarson, who arrived here with his family and slaves in 874. He was the first to use the name Reykjavik (the word meant “smoking bay”).